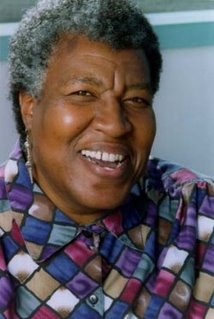

Bebe Moore Campbell

Bebe Moore Campbell (February 18, 1950- November 27, 2006) was the author of three New York Times bestsellers, Brothers and Sisters, Singing in the Comeback Choir, and What You Owe Me, which was also a Los Angeles Times "Best Book of 2001." Her other works include the novel Your Blues Ain't Like Mine, which was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year and the winner of the NAACP Image Award for Literature; her memoir, Sweet Summer, Growing Up With and Without My Dad; and her first nonfiction book, Successful Women, Angry Men: Backlash in the Two-Career Marriage. Her essays, articles, and excerpts appear in many anthologies.

Ms. Campbell's interest in mental health was the catalyst for her first children's book, Sometimes My Mommy Gets Angry, which was published in September 2003. This book won the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) Outstanding Literature Award for 2003. The book tells the story of how a little girl copes with being reared by her mentally ill mother. Ms. Campbell is a member of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and a founding member of NAMI-Inglewood. Her latest book, 72 Hour Hold, also deals with mental illness.

Ms. Campbell's first play, "Even with the Madness," debuted in New York in June 2003. This work revisited the theme of mental illness and the family.

As a journalist Ms. Campbell wrote articles for The New York Times Magazine, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, Essence, Ebony, Black Enterprise, as well as other publications. She was a regular commentator for Morning Edition a program on National Public Radio.

Ms. Campbell was born and reared in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and received a Bachelor of Science (B.S.) degree in elementary education from the University of Pittsburgh. She lived in Los Angeles, California with her husband, Ellis Gordon Jr. and had a son and a daughter, actress Maia Campbell. She was an honorary member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Incorported.

November 28, 2006

Bebe Moore Campbell, Novelist of Black Lives, Dies at 56

By MARGALIT FOX

Bebe Moore Campbell, a best-selling novelist known for her empathetic treatment of the difficult, intertwined and occasionally surprising relationship between the races, died yesterday at her home in Los Angeles. She was 56.

The cause was complications of brain cancer, said Linda Wharton-Boyd, a longtime friend.

Along with writers like Terry McMillan, Ms. Campbell was part of the first wave of black novelists who made the lives of upwardly mobile black people a routine subject for popular fiction. Straddling the divide between literary and mass-market novels, Ms. Campbell’s work explored not only the turbulent dance between blacks and whites but also the equally fraught relationship between men and women.

Throughout her work, Ms. Campbell sought to counter prevailing stereotypes of black people as socially and economically marginal. Though critics occasionally faulted her characters as two-dimensional, her novels were known for their crossover appeal, read by blacks and whites alike.

Often called on by the news media to discuss race relations, Ms. Campbell was for years a familiar presence on television and radio. With the publication of her most recent novel, “72 Hour Hold” (Knopf, 2005), she also became a visible spokeswoman on mental-health issues. The novel, about bipolar disorder, was inspired by the experience of a family member, Ms. Campbell said.

Originally a schoolteacher and later a journalist, Ms. Campbell made her mark as a writer of fiction with her first novel, “Your Blues Ain’t Like Mine” (Putnam), published in 1992. Rooted in the story of Emmett Till, the book tells of a black Chicago youth killed by a white man in Mississippi in 1955. After the murderer is acquitted at trial, the narrative follows his increasing dissolution.

“I wanted to give racism a face,” Ms. Campbell said in an interview with The New York Times Book Review in 1992. “African-Americans know about racism, but I don’t think we really know the causes. I decided it’s first of all a family problem.”

Reviewing the novel in The Book Review, Clyde Edgerton wrote: “By showing lives lived, and not explaining ideas, Ms. Campbell does what good storytellers do — she puts in by leaving out.”

Ms. Campbell’s other novels, all published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, are “Brothers and Sisters” (1994), written in the wake of the Los Angeles riots of 1992; “Singing in the Comeback Choir” (1998), about a black television producer feeling cut off from her roots; and “What You Owe Me” (2001), about the friendship between two women, one African-American, the other a Jewish Holocaust survivor, in the 1940’s.

Elizabeth Bebe Moore was born in Philadelphia on Feb. 18, 1950, to parents who divorced when she was very young. Bebe spent each school year in Philadelphia with her mother, grandmother and aunt — strong, upright women she collectively called “the Bosoms” — who set her on a course of study, discipline and staunch middle-class respectability.

She spent summers in North Carolina with her father, who had been paralyzed in an automobile accident. There, she was enveloped in a heady world of beer, laughter and cigar smoke. She documented her contrasting lives in her memoir, “Sweet Summer: Growing Up With and Without My Dad” (Putnam, 1989).

After earning a bachelor’s degree in elementary education from the University of Pittsburgh in 1971, Ms. Campbell taught school in Atlanta for several years before embarking on a career as a freelance journalist. Her first book was a work of nonfiction, “Successful Women, Angry Men: Backlash in the Two-Career Marriage” (Random House, 1986).

She also wrote two picture books for children, “Sometimes My Mommy Gets Angry” (Putnam, 2003; illustrated by E. B. Lewis); and “Stompin’ at the Savoy” (Philomel, 2006; illustrated by Richard Yarde).

Ms. Campbell’s first marriage, to Tiko Campbell, ended in divorce. She is survived by her husband, Ellis Gordon Jr., whom she married in 1984; her mother, Doris Moore of Los Angeles; a daughter from her first marriage, Maia Campbell of Los Angeles; a stepson, Ellis Gordon III of Mitchellville, Md.; and two grandchildren.

Despite the subject matter of her books, Ms. Campbell expressed hope about the future of American race relations. In an interview with The New York Times in 1995, she described her motivation for writing “Brothers and Sisters,” the story of the friendship between a black banker and her white colleague.

“It was my attempt to bridge a racial gap,” Ms. Campbell said. “That’s the story that never gets told: how many of us really like each other, respect each other.”

You can read one of her interviews here.